THE WINDBER

MINERS’ STRIKE FOR UNION, 1922-23

1. Joining The National Strike

2. Grievances

4. Continuing After Exclusion From the National Settlement

5. New York City Campaign and Inquiry

William Parks’ letter from Beaverdale.

On

the eve of the national strike, groups of Windber miners went on their own

initiative to the Beaverdale UMWA local (and others) to report their readiness

to join the strike and their desire for union.

Source: United Mine Workers of America, District 2 Records, Stapleton Library, Special Collections, Indiana University of Pennsylvania. \

District 2’s strike call to non-union miners.

On

April 1, 1922, organizers from UMWA District 2 invaded Windber and

“Siberia”--their term for Somerset County.

They handed out these brochures until they were arrested or chased away

by the Coal and Iron Police or other company officials.

Source: United Mine Workers of America, District 2 Records, Stapleton Library, Special Collections, Indiana University of Pennsylvania.

Joseph Zahurak quotation explaining How the Haulage Men....

JOSEPH ZAHURAK EXPLAINS

HOW THE HAULAGE MEN

LED THE WINDBER MINERS OUT ON STRIKE

They [the miners] come out on the field in 1922. That's when they first get out there. The haulage men of Berwind-White--the haulage men, I mean mine motormen and spraggers. They was in contact with all the miners in the mine because they always ordered their cars, the amount of empty cars that they wanted or the loads that they pulled out, the haulage men. So the haulage men got together in 1922 to get it organized to come out on strike, and we avoided these people that--informers. Make sure they didn't contact them so they don't know anything about it. So in 1922, when April 1st come, a union holiday, they surprised Berwind-White, shut them down completely [emphasis]. Even the captive mines, Bethlehem Steel, US Steel, and all them. They was all shut down. And Frick Coal Company in Pittsburgh. So in 1922, it was quite a battle. . . .

Joseph

Zahurak, a spragger and 1922 strike activist who later served as president of

UMWA Local 6186 (1938-1977), offered this description of how the Windber strike

began.

Source: Joseph Zahurak, Interview by Mildred Beik, October 7, 1986, Millie Beik Collection, Stapleton Library, Special Collections, Indiana University of Pennsylvania.

The New York Herald’s article on the non-union walkout.

:

In April 1922, the New York Herald and other newspapers throughout the country

expressed great surprise that non-union miners in Windber and elsewhere had

joined the strike for union. In

doing so, southern and eastern European immigrants were defying prevailing

American ethnic stereotypes about their “docility.”

Source: New York Herald Tribune, April 26, 1922[?], in Scrapbook, Powers Hapgood Papers, Lilly Library, Manuscripts Department, Indiana University, Bloomington, Ind.

List of six grievances

Such a condition in a free country could not last forever and the miners at non-union mines were only waiting for the opportunity to assert their rights. The occasion was the great coal strike of last year. Only a short time after the strike was declared in the union fields the miners in the non-union mines joined us. The strike of the union miners was for a continuation of the wage rates; that of the non-union miners was more - it was also a strike to end fear. Nearly 25,000 miners of the non-union fields in our district answered the strike call, and a great number of them, after 14 months are still on strike.

To be more specific they struck

1. For collective bargaining and the right to affiliate with the union.

2. For a fair wage.

3. For accurate weight of the coal they mine. (Experience teaches us that this can be assured only when the miners have a checkweighman.)

4. Adequate pay for "dead work."

5. A system by which grievances could be settled in a peaceful and conciliatory spirit by the mine committee representing the miners and a representative

of the operator.

6. But above all they struck to assure their rights as free Americans against the state of fear, suspicion and espionage prevailing in non-union towns. Against a small group of operators controlling life, liberty, and pursuit of happiness of large numbers of miners. To put an end to the absolute and feudal control of these coal operators.

The last mentioned point being of greatest significance

not only to miners but to all American citizens. I shall take it

up first. It is by reason of such absolute control that the other

grievances exist in non-union fields. How does this control

operate in practice? We will quote an authority not connected with.On

May 28, 1923, District 2 UMWA President John Brophy presented a statement to the

U.S. Coal Commission, which was studying the “sick” coal industry.

Source: John Brophy, Clearfield, Pa., to Hon. John Hammond, Chairman, and Members of the United States Coal Commission, Washington, D.C., May 28, 1923, in Powers Hapgood Papers, Lilly Library, Manuscripts Department, Indiana University, Bloomington, Ind.

Lynn

Adams’s State Police letter to coal operators

Berwind-White’s

answer to Lynn Adams’s State Police letter to coal operators

Before

the strike, on March 18, 1922, Lynn G. Adams, Superintendent of the State

Police, wrote a secret letter to the coal operators asking for confidential

information about their operations to help the police during the strike.

The letter strongly supports the strikers’ view that the State Police

were not impartial upholders of law and order but allies of the coal

corporations. Here is Berwind-White’s

response to Adams’s letter.

Source: Pennsylvania State Police Records, RG 30, Pennsylvania State Archives, Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, Harrisburg, Pa.

Windber Local 4207 letter asking for inclusion in any strike settlement

In

July 1922, there was increasing talk about government arbitration and concern

about some sort of national settlement of the strike. To press for their inclusion in any final strike settlement,

Windber UMWA Local 4207 and other new-founded Somerset County UMWA locals sent

letters to President Harding, International UMWA President John L. Lewis, and

District 2 UMWA President John Brophy.

Source: United Mine Workers of America, District 2 Records, Stapleton Library, Special Collections, Indiana University of Pennsylvania.

For

publicity and relief-raising efforts, this photo of several thousand Windber

miners, dressed for the occasion, was taken in an open field soon after their

decision to continue the strike for union.

Source: United Mine Workers’ Journal, October 1, 1922.

UMWA

District 2, friends, and relatives were unable to help relocate all those mining

families who were evicted in Windber. By

September 1922, tent colonies like this one dotted the Windber landscape.

Source: David Hirshfield, Statement of Facts and Summary of the Committee Appointed by Honorable John F. Hylan of New York to Investigate the Labor Conditions at the Berwind-White Company’s Coal Mines in Somerset an Other Counties, Pennsylvania: (New York, December 1922), p. 10.

PEARL LEONARDIS

ON HELPING EVICTED FAMILIES

When they went on strike, Berwind threw [out] everything. They [Berwind people] went there and throw everything out from these families. That was a shame. You don’t do stuff like that, you know. You stop the book [storebook]. You don’t give them nothing. You don’t give them the power, okay, the light, but don’t throw their stuff out. Everything was throwed out, and those people were stranded. They were out there picking up their things.

So we had to, I told my husband, "Well," I says, "yonze go pick some families up."

So they went out, too, and they bring me a family.....

This lady had two children, and she had a brother-in-law and her and her husband. So I says, "O.K.," I said, "I’ll give you." I took the dining room, all the parlor. I pushed everything, bring every piece of furniture upstairs, and I made her a bedroom of my parlor....We took her furniture, everything that they could find up there and brought everything in.

I says, "I have a bunk bed." I says, "I’ll put him [the brother-in-law] in with our men upstairs." And I told them, "And don’t yonze say no. He’s a brother." I says, "We, yonze, are all on strike, and he’s on strike, and we have to take care of these men." And we had a family. Then this other one [the neighbor] did like I did, and we put up another family, you know.

New York City Campaign and Inquiry

Windber Pickets on Broadway

Source: Unidentified newspaper photo in Powers Hapgood Papers, Lilly Library, Manuscripts Department, Indiana University, Bloomington, Ind.

Photo of the Hirshfield Committee entering one of the Windber mines

Because

of the Windber miners’ campaign, E. J. Berwind’s refusal to negotiate, and

his scandalous conflict-of interest role on the Interborough Rapid Transit

System’s board, Mayor John Hylan of New York City sent a committee of

prominent city officials to investigate the living and working conditions of the

Berwind-White miners. This photo

shows that committee, entering a mine in Windber on November 1, 1922.

Source: David Hirshfield, Statement of Facts and Summary of the Committee Appointed by Honorable John F. Hylan of New York to Investigate the Labor Conditions at the Berwind-White Company’s Coal Mines in Somerset an Other Counties, Pennsylvania: (New York, December 1922), p.22.

“Worse Than Slaves” article from the New York Times

The

shocking conclusion of the New York City committee’s report--that the

“living and working conditions of the miners employed in the Berwind-White

Coal Mining Company’s mines were worse than the conditions of the slaves prior

to the Civil War”--appeared on page 1 of the New

York Times and other newspapers throughout the nation on January 2, 1923.

Source: New York Times, January 2, 1923, p. 1.

“A Lost Strike is Never Lost” (an old labor saying)

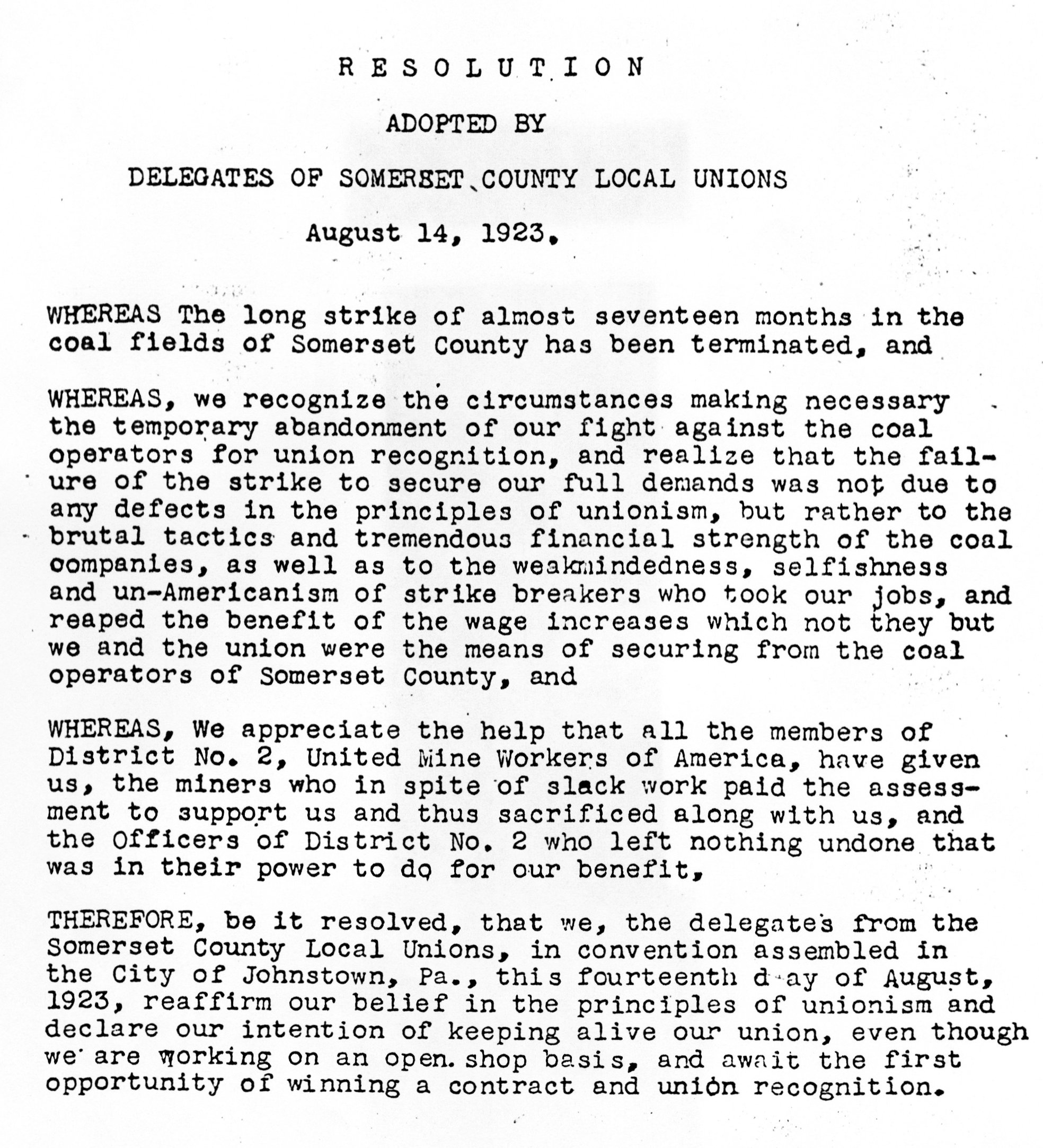

Resolution Adopted by Delegates of Somerset County Local Unions

Windber

and Somerset UMWA locals reaffirmed their ongoing desire for union in this

resolution, even as they found it necessary to call off their 16-month long

strike for union.

Source: Powers Hapgood Papers, Lilly Library, Manuscripts Department, Indiana University, Bloomington, Ind.

Joseph Zahurak Quotation about the Coming of the Union in 1933

JOSEPH ZAHURAK EXPLAINS

HOW THE UNION CAME TO WINDBER

So, then, later on, after we come into it here, where we finally, after all these strikes from 1927 to 1933, when finally [warmly said], the dark clouds disappeared.Oh, [enthusiastically] the miners in Windber, and we got our sympathetic president that got in there. Yah, Franklin Delano Roosevelt. And they got that law [the National Industrial Relations Act] passed where you could organize. You're allowed to organize if you want to organize. And I'm telling you, that law was passed, and the union come in.The United Mine Workers was short on funds and money. So they borrowed $500,000 from the American Federation of Labor to put men out in the field for expenses to go out and talk to these miners. And they brought cards for us to sign the miners up, who all wanted the union. And I'm telling you them cards went fast! Everybody was signing up. That's 1933 when they knew that they was finally safe. It could be done....We finally got our first union meeting in Slovak Brick Hall. And after a couple of meetings in there in July, in July 1933, we received our charter. And Berwind-White finally recognized the union.